Recently I've been trying to come to

grips with what I consider to be a major historiographical problem

which applies very directly to the time period which I have made the

focus of this study. The problem lies in what we choose to call this

period of Russian history. The answer that most immediately comes to

the minds of many would be “Pre-Revolutionary Russia,” and

admittedly this is the term that I have utilized most frequently up

until now. However, the use of this term implies creates several

problems with the way in which we view Russia's history, and thus how

we then attempt to place the work of Chekhov into that context.

When we define the period of time

before the revolutions only in terms of the revolutions themselves,

it implies a degree of inevitability of the popular and Bolshevik

revolutions. While Marxist theory, which views revolution as truly

inevitable, would support this and certainly Soviet historians would

have appreciated the placement of emphasis with this term, the

realities do not support this choice. First of all, the term that is

sometimes used rather flippantly, “the inevitability of history,”

can only be used in a way that does not appear foolish, in the past

tense. This is because at the time of any historical event, a

countless number of things could take place, the result of that

moment is not defined. But beyond purely philosophical issues of this

approach, the use of pre-revolutionary and the predetermined nature

that it implies also happens to contradict the facts of Russia at

this time. The Revolutions that took place in the early 20th

Century were by no means the type of communist revolutions that Marx

was such an adamant supporter of. In fact, not only was the lack of a

switch to a more free, market-based, economy before the rise of

communism, which is indicative of Marxist theory, but the idea the

transition of power took the form of a coup and subsequent civil war

also disqualifies it as an inevitable Marxist revolution.

Furthermore, the Soviet's utilization of this term, painting a

picture of a world leading up to their regime, is equally suspect.

This is given that there was decidedly not a popular uprising of the

Bolshevik's who then wrested power from the Tsar, but rather the

protests and general revolutionary sentiment caused the Tsardom to

collapse and only almost a year later did the Bolshevik's interrupt

the creation of a new government through a constituent assembly and

seize power. Sheila Fitzpatrick's characterization of the transition

of power out of the hands of the Tsar is revealing: “In the days

following Nicholas' abdication, the politicians of Petrograd were in

a state of high excitement and frenetic energy. Their original

intention had been to get rid of Nicholas rather than the monarchy.”

It seems clear that this term is

insufficient to characterize the time and is probably more damaging

than it is beneficial for our purposes. The question then becomes,

what do replace it with? Some historians, while not really addressing

this question, but recognizing a problem with the previous term, have

adopted the title of “Late-Tsarist” Russia to describe the reign

of Nicholas II and the transition to the revolution. While there is

no arguing the fact that Nicholas II was indeed the last Tsar of

Russia this does not solve the problem so much as it does invert it.

So what are we left with? Simply refer to the time period by its

numerical designations? Simply refer to the period as “Late 19th”

and “Early 20th” centuries. Such an answer does not so much solve

the problem as it does avoid it. So, in search of possible answers I

turned to the world of art in Russia.

While I had, and have no hopes in

necessarily finding the

answer in this way, it seemed to me that perhaps, especially

considering the artistic nature of the medium we are attempting to

place into context, we might be well served to look at some of the

artistic movements in Russia at this time as a jumping off point.

Through

a bit of investigation, one of the first artist movements of Russia

at the end of the reign of Nicholas II was that of “The Jack [or

knave] of Diamonds.” Mounded in Moscow in 1910 and functioning as a

collective up until December of 1917 (a date with should not strike

us as coincidental). The group began, influenced by the French

Cubists, as a means for artists who had been labeled as “too

leftist” to be showcased in mainstream galleries, to find places to

have their work displayed. The group was fairly prolific for the few

years they were in prominence and were connected with the beginnings

of the early Avant-garde in Russia. The group did seem to foster a

sort of revolutionary spirit and their name helped to showcase this

to their contemporaries: "The title Knave of Diamonds [was

regarded] as a symbol of young enthusiasm and passion, 'for the knave

implies youth and the suit of diamonds represents seething blood.'”

The combination of the nature of their work, their seeming desire for

change and, as I mentioned, the fact that the group faltered (out of

lack of need on some level, but also with many of the members moving

on to the World of Art group) led them to be a leftist democratizer

of the arts in Russia.

While

this art movement holds some appeal as a replacement to the moniker

of pre-revolutionary, I think there is something to be gained in

being able to observe the change of movements. For example in the

traditional sense of terms, we go from pre-revolutionary/late-tsarist

Russia, into revolution and then Early Soviet Russia. However, though

the Knave of Diamonds movement seemingly supported revolutionary

sentiment at the time they also fade into the larger landscape of

artistic movements when the revolution takes place in 1917.

Thus

I think the more interesting choice lies with a pair of movements

which, though stylistically in many ways inform one another,

philosophically contradict one another. They are the Suprematism and

the Constructivism movements.

The

Suprematism or Супрематизм

movement began in roughly 1915 in Moscow and was founded by Kazimir

Malevich. The Movement, as defined in Malevich's 1927 work The

Non-Objective World as art that

is based upon “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling” and not

simply on depiction of objects. Visually, artwork born out of this

tradition tends to be very geometric, focusing on basic, familiar

forms. [I've included a small sampling of some of Malevich's work

below.]

Interestingly, this movement places an emphasis on feeling,

to borrow a term from a distinctly different tradition, an almost

cathartic expression. This seems in keeping to me with the feelings

conjured up when reading depictions, such as Fitzpatrick's, of the

years leading up to the revolutions. Furthermore, the Suprematists

saw themselves as social protestors as well. After Socialist Realism

became the artistic medium allowed by the state and groups such as

the Suprematists where suppressed, they still protested – albeit in

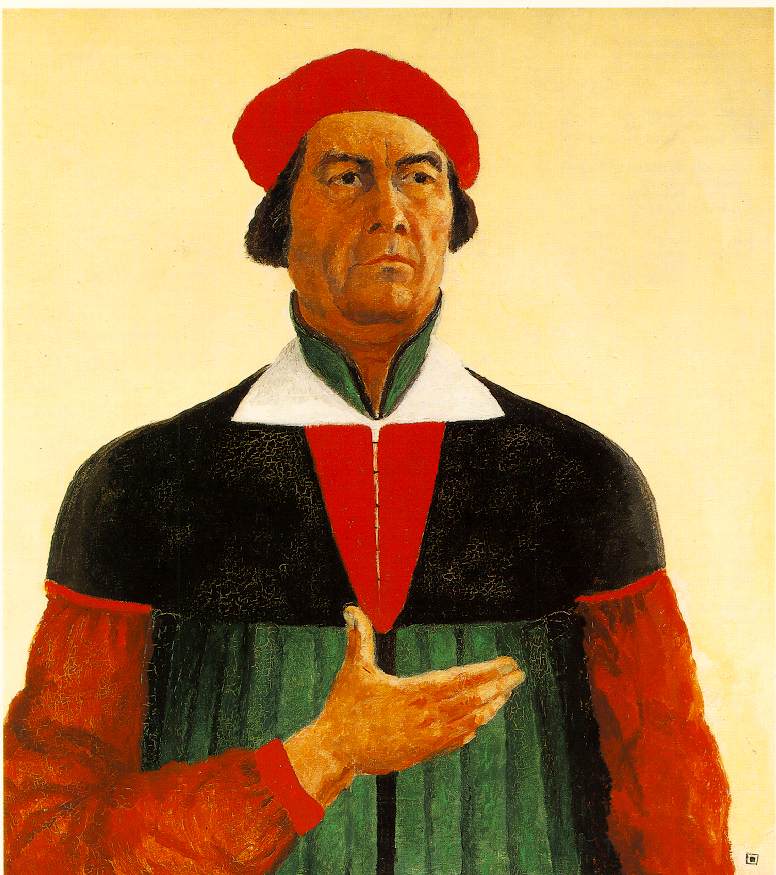

a more subtle manner. I've included Malevich's 1933 self portrait, in

which he is depicted rather traditionally, however if you look in the

lower right hand corner he signs the piece, not with his his name,

but with a small black square inside a white one.

The

similar artistic movement that I would argue could be used to

represent the change that took place in the wake of the revolution is

that of the Constructivists. Beginning in 1919, the timing fits

appropriately and though they adopt many of the stylings of the

Suprematists, their artistic philosophy differs drastically. It is

most easily explained in the distinctions between the two. As

Malevich's book was titled “The Non-Objective World,”

Constructivism on the other hand has a great deal of emphasis upon

the object and most importantly the practical application of the

object. Explained by some as the creation of a group of

artist[s]-as-engineer. This proves interesting because of the

familiar sentiment towards what will eventually be realized under

Stalin and Socialist Realism, when artists were to be an “artist in

uniform” and use their talents to serve the interests of the state

and of Communism. Constructivism evolved even further as Communism

was built up after the revolution, choosing to lend its talents and

stylings to those things that it deemed productive and beneficial.

I've included a poster of that era here: [to the support of the Red

army during the civil war]

We see

this distinction drawn out further through Malevich's defiance of

this ideal:

“Art no longer

cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to

illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further

to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in

and for itself, without 'things'”

I

think the distinction here, between these two artistic movements is

incredible and could prove revelatory to this study. I have hunted

down a copy of Malevich's text to see what else I might glean from

it. However, it would seem to me that the earlier movement of

Suprematism embodies true revolutionary sentiment, with an empahsis

upon supreme feeling rather than practical application.

Constructivism on the other hand utilizes the tools of revolutionary

sentiment in order to further the goals of the State, or faith, or

whatever structure they choose to support, with the emphasis upon

progress. This is clarified by the fact that the Constructavists

arose out of the revolution and the Suprematists, unlike the artist

of the Knave of Diamonds, did not disappear in the world after the

revolution, but rather fought against what they must have viewed as a

bastardization of their movement.

As I

said, I plan to explore this further through reading of Malevich's

text, but the co-opting of these terms for our purpose seems to be an

improvement over the more historically troublesome time-period

designations used more commonly.

No comments:

Post a Comment